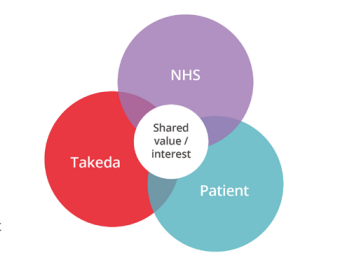

An outline of Takeda's offering for working in partnership to optimise outcomes for patients with ADHD

Takeda values

- Integrity

- Fairness

- Honesty

- Perseverance

Takeda's commitment to ADHD

- Medicines

- Multidisciplinary educational support programmes

- ADHD Clinical Nurse Educators

- Support for ADHD Service Development

- Parliamentary and patient advocacy

Patient interests

- Equality and ease of access to assessment, diagnosis and treatment

- Improved health outcomes

- Reducing the burden of ADHD

- Living the best life they can

NHS priorities

- Nice guideline on the diagnosis and management of ADHD (NG87)*1

- Effective integrated care models

- Reduce demand and capacity issues, including waiting lists for patient access to diagnosis and treatment

- Reduce unplanned care and associated spend

- Reduce medicines wastage linked to GIRFT†²

- Reduce variation and inequality in care / Core20PLUS5‡3

- Paucity of data on ADHD due to under- / misdiagnosis

- Workforce retention and job satisfaction / development

- Digital innovation

Burden of ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a lifelong condition, with wide-reaching implications for a person's life. ADHD has been shown to impact outcomes in education and the workplace (e.g., achievement of academic milestones beyond high school or full-time employment),4 as well as social functioning, with the potential to drive health inequalities and have further repercussions for the health and social support systems providing care.5

ADHD is highly comorbid with other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders across the lifespan.6 The most common comorbidities among children and adolescents are learning disabilities and oppositional defiant disorder, although anxiety, depression, conduct disorder, substance use disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and tic disorder are also common.6 Evidence suggests that adults living with ADHD are at a much higher risk than the general population of experiencing co-occurring mental health conditions, such as depression,7 anxiety7 and suicidal tendencies,8 which can be exacerbated if the underlying symptoms of ADHD are not managed.7 Adults lacking support and/or interventions for ADHD are also at a higher risk of obesity,9 smoking and substance misuse,10 posing further threats to their long-term health outcomes.

In addition to a high rate of disruptive behaviour disorders,6 many children with ADHD find life at school and areas of homework, family routine and playing with other children significantly more challenging than peers without mental health problems,11 indicating the wider societal implications of ADHD. In adolescence, ADHD symptoms may be predictive of early parenthood and increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases,12 as well as increasing the likelihood of criminal behaviour.13 In addition to the health risks linked to ADHD, studies have shown that adults with unmanaged ADHD are at a higher risk than the general population of dropping out of school,14 unemployment15 or transport accidents,16 and have a greater propensity towards criminal behaviours.17 There are also wider societal costs associated with unmanaged ADHD, which affect schools, workplaces, economic productivity, the criminal justice system and the healthcare system.5 For example, it is estimated that 25% of people in prison have ADHD,18 in comparison with a prevalence rate of 3–5% in the general population.19

ADHD is estimated to cost the UK criminal justice system £11.7 million per annum,20 in addition to education and healthcare costs that are calculated at a further £670 million spend annually.21 As such, the high unmet need in ADHD is estimated to cost the UK economy billions of pounds each year.5

By contrast, the appropriate recognition and management of ADHD has been shown to improve outcomes in psychiatric disorders,7 suicidality22 and key indicators of population health, including obesity.9 The effective management of ADHD can also lead to higher attainments in education and at work23 and lower levels of criminality.24

ADHD is likely to be underdiagnosed and undertreated in specific populations, such as adults,25 girls and women,1 within prison populations26 and within colleges/universities.27 Although boys are more likely to receive an ADHD diagnosis than girls, it may be because symptoms present differently in girls.28,29 Many of the challenges associated with unmanaged ADHD in adults stem from the critical lack of diagnosis of the condition in adults. Although ADHD is thought to affect between 3–5% of the general population globally,19 a UK population-based cohort study reported adult ADHD diagnostic rates of 0.3% in males and 0.07% in females, and ADHD pharmacological treatment rates of 0.04% in males and 0.01% in females between 2000 and 2018 in primary care.25

Working in partnership

In response to the outlined challenges, Takeda believes there is an important role for Takeda to play in making these aspirations a reality.

The overarching goal of Takeda's Service Development Team is to help ADHD services in the UK – to work towards the provision of effective and sustainable care by reducing health inequalities and standardising care for people with ADHD across the UK. Takeda aims to achieve this by developing meaningful strategic and scientific partnerships; we develop value-based solutions with healthcare providers to achieve their ambitions for excellent patient care.

The Takeda Service Development Team has developed several programmes and tools to meet the needs of organisations across the health economy (including the NHS, private healthcare providers, healthcare charities, prisons and universities), such as:

- Integrated care system / health board ADHD service treatment ranking tool

- Support with examples of shared care protocols and NICE compliant ADHD pathways

- ADHD expertise to support pathway efficiencies and redesign

- Networking and sharing best practice with other services

- NICE quality standards service benchmarking tool

- Project support documents

- Multidisciplinary educational programmes and support

- Clinical Nurse Educator resources

- Patient and clinician satisfaction surveys

- Advice on outcome measurement and data capture

Ways of working

The Takeda Service Development Team would be delighted to meet with you, virtually or in person, to understand your needs and scope out areas that we feel we could potentially offer support, working with you alongside your organisation.

Please note that the role of the Takeda Service Development Team is non- promotional. We operate within the Takeda Medical Affairs Team and, as such, are not linked to the commercial arm of the business and are therefore unable to discuss Takeda medicines. Our primary objective is to ensure people receive a timely diagnosis and management for ADHD by increasing / optimising service capacity.

Next steps

Please contact your local Takeda Service Development Team member via email at UK.service.development@takeda.com for a bespoke plan of action that could support your organisation and meet the needs of your patient population.

*The NICE guideline on the diagnosis and management of ADHD (NG87)1 provides a comprehensive blueprint for good care and support for ADHD across the treatment pathway; however, there are challenges in meeting these standards across England.

†Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) is a national programme designed to improve the treatment and care of patients through in-depth review of services, benchmarking, and presenting a data-driven evidence base to support change.2

‡Core20PLUS5 is a national NHS England approach to inform action to reduce healthcare inequalities at both national and system level. The approach defines a target population – the ‘Core20PLUS’ – and identifies five focus clinical areas requiring accelerated improvement.3

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; GIRFT, Getting It Right First Time; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NHS, National Health Service.

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline (NG87). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. 14 March 2018 (Last updated September 2019).

- Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) website. Available at: https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk [Accessed 17 May 2024].

- National Health Service (NHS) England website. Core20PLUS5 (adults) – an approach to reducing healthcare inequalities. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/core20plus5/ [Accessed 17 May 2024].

- Biederman J, Faraone S. The effects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on employment and household income. MedGenMed 2006; 8(3): 12.

- Shire and Demos. Your Attention Please: The Social and Economic Impact of ADHD. 2018. Available at: https://demos.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Your-Attention-Please-the-social-and-economic-impact-of-ADHD-.pdf [Accessed 17 May 2024].

- Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (CADDRA). Canadian ADHD Practice Guidelines, 4.1 Edition. January 2020.

- Katzman M, Bilkey TS, Chokka PR, et al. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry 2017; 17(1): 302.

- Sun S, et al. Association of psychiatric comorbidity with the risk of premature death among children and adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2019; 76(11): 1141–1149.

- Cortese S, Moreira-Maia CR, St Fleur D, et al. Association between ADHD and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2016; 173(1): 34–43.

- Sundquist J, Ohlsson H, Sundquist K, Kendler KS. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk for drug use disorder: A population-based follow-up and co-relative study. Psychological Medicine 2015; 45(5): 977–983.

- Caci H, Doepfner M, Asherson P, et al. Daily life impairments associated with self-reported childhood/adolescent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and experience of diagnosis and treatment: results from the European Lifetime Impairment Survey. Eur Psychiatry 2014; 29(5): 316–323.

- Chen MH, Hsu JW, Huang KL, et al. Sexually transmitted infection among adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018; 57(1): 48–53.

- Mohr-Jensen C, Muller Bisgaard C, Boldsen SK, Steinhausen HC. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood and adolescence and the risk of crime in young adulthood in a Danish nationwide study. J AM Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019; 58(4): 443–452.

- Young, S., et al. ADHD: making the invisible visible. An Expert White Paper on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): policy solutions to address the societal impact, costs and long-term outcomes, in support of affected individuals. 2013. Available at: http://www.russellbarkley.org/factsheets/ADHD_MakingTheInvisibleVisible.pdf [Accessed 17 May 2024].

- Gjervan B, Torgersen T, Nordahl HM, Rasmussen K. Functional impairment and occupational outcome in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord 2012; 16(7): 544–552.

- Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, D’Onofrio BM, et al. Serious transport accidents in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the effect of medication: a population-based study. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71(3): 319–325.

- Mohr-Jensen C, Steinhausen HC. A meta-analysis and systematic review of the risks associated with childhood attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder on long-term outcome of arrests, convictions, and incarcerations. Clin Psychol Rev 2016; 48: 32–42.

- Young S, Cocallis KM. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the prison system. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2019; 21(6): 41.

- Raman S, Man KKC, Bahmanyar S, et al. Trends in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder medication use: a retrospective observational study using population-based databases. Lancet Psychiatry 2018; 5(10): 824–835.

- Young S, Gonzalez RA, Fridman M, et al. The economic consequences of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in the Scottish prison system. BMC Psychiatry 2018; 18(1): 210.

- Telford C, Green C, Logan S, et al. Estimating the costs of ongoing care for adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013; 48(2): 337–344.

- Chen Q, Sjölander A, Runeson B, et al. Drug treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and suicidal behaviour: register based study. BMJ 2014 Jun 18; 348: g3769.

- Shaw M, Hodgkins P, Caci H, et al. A systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of treatment and non-treatment. BMC Medicine 2012; 10: 99.

- Young S, Gudjonsson G, Chitsabesan P, et al. Identification and treatment of offenders with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the prison population: a practical approach based upon expert consensus. BMC Psychiatry 2018; 18(1): 281.

- McKechnie DGJ, O’Nions E, Dunsmuir S, Petersen I. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder diagnoses and prescriptions in UK primary care, 2000–2018: population-based cohort study. BJPsych Open 2023; 9(4): e-121, 1–10.

- Young SJ, Adamou M, Bolea B, et al. The identification and management of ADHD offenders within the criminal justice system: a consensus statement from the UK Adult ADHD Network and criminal justice agencies. BMC Psychiatry 2011; 11: 32.

- Sedgwick-Müller JA, Müller-Sedgwick U, Adamou M, et al. University students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a consensus statement from the UK Adult ADHD Network (UKAAN). BMC Psychiatry 2022; 22(1): 292.

- Rucklidge JJ. Gender differences in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2010; 33(2): 357–373.

- Quinn PO, Madhoo M. A review of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in women and girls: uncovering this hidden diagnosis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2014; 16(3): PCC.13r01596.

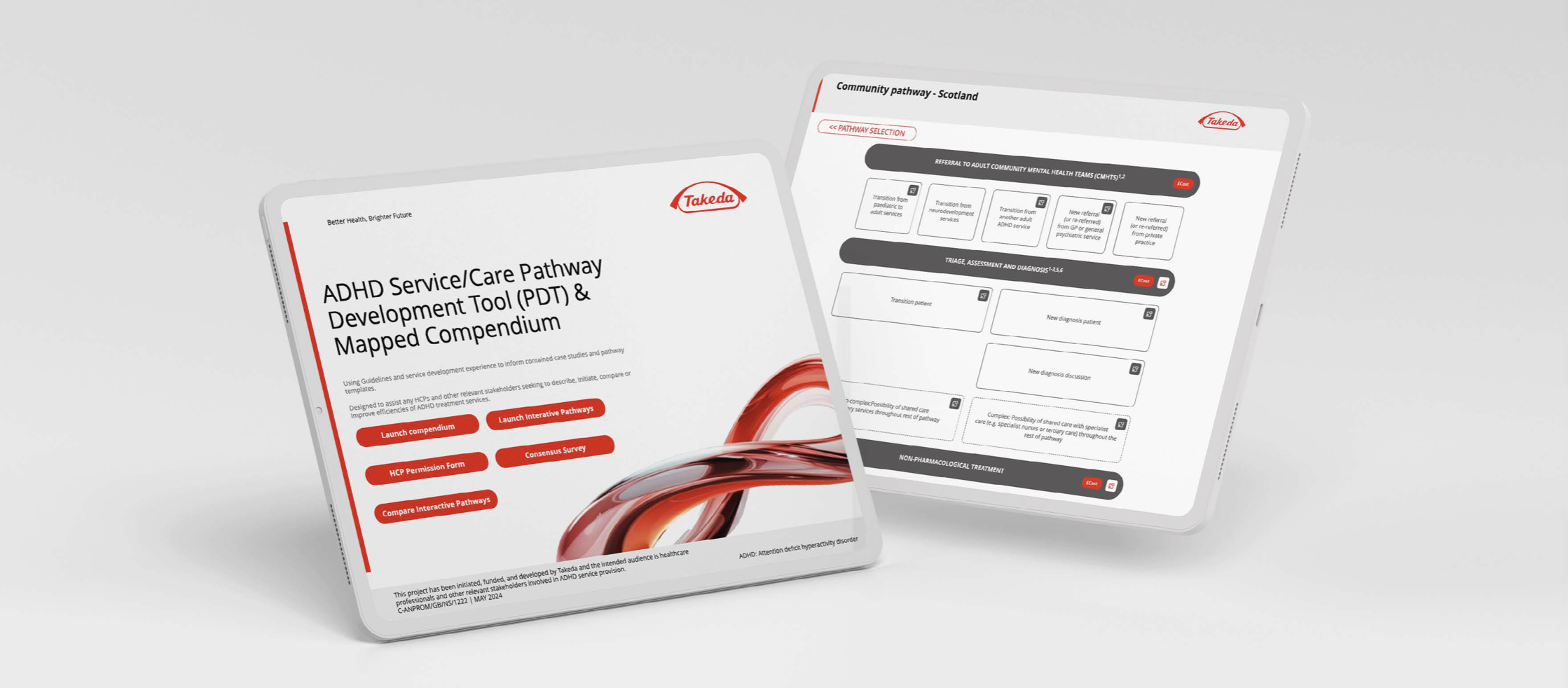

Pathway Development Tool

This tool has been developed using established guidelines and service development experience, incorporating case studies and pathway templates. It supports the creation and redesign of pathways for Adults, Children and Young People (CYP), Universities, and Prisons.

Its purpose is to provide guidance and support for healthcare professionals (HCPs) and other stakeholders involved in ADHD services.

The primary goal of this tool is to assist HCPs and relevant stakeholders in describing, initiating, creating, comparing, and enhancing the efficiency of ADHD services in terms of cost and time.

To uncover more about the tool and how we can possibly support please reach out to our Service

Development Managers.